land

Devil's Den

February 12, 2021

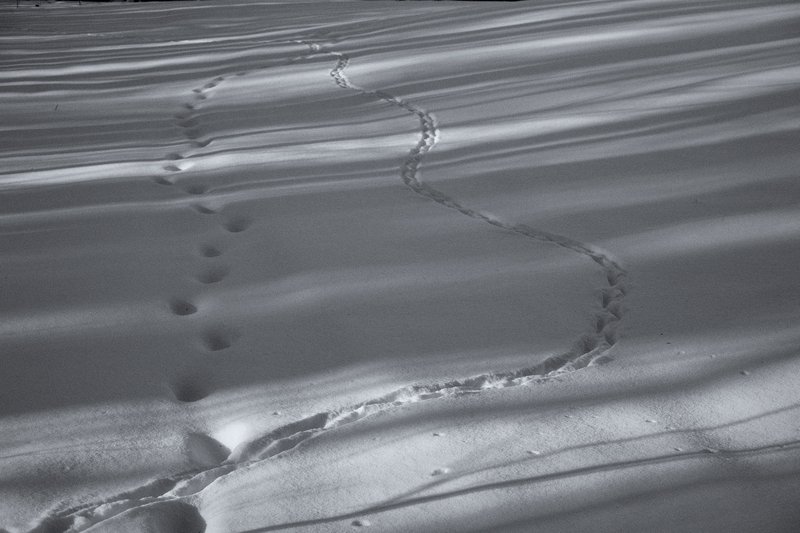

I set out for Devil's Den, through one foot of untrammeled snow. Only coyote and deer have passed through here, crossing perpendicular to my trail. Since humans have the right of way on this oversized human trail, it's appropriate for me to blaze it after these several snow storms. Walking was slow-going but steady, through temperatures well-below freezing. At least it's sunny and dry today.

There's quite a bit of deer traffic. I wonder about them, this time of year. Are they getting desperate? Judging from their signs, they're dehydrated. Halfway down the trail, a small wet area offers a meager water source for the thirsty.

Walking further, the land opens up to the sky, and the western cliffs become more impressive. This is porcupine country. They don't seem to wander like others – a little snow-packed highway leads straight from their cave to their usual browsing areas. They probably make a regular circuit, leaving down one road, circling back above their cave, then descending into it. Many times I've sat in the cave mouth, on a vast field of porcupine poop, listening for them. They make all sorts of little noises; maybe they're dreaming, or maybe they're irritated about somebody snooping around. Either way, I love them, their confidence and resilience.

After the porcupine home, there's a strange stone wall, emerging out of the cliff, descending the hill, leaving an opening for the trail, then descending further, until it ends downslope of the trail. I have some ideas about the wall, one of which I'll mention later.

If there weren't so much snow on the ground, the stream on the other side of the wall would start to become obvious. At times, you wouldn't notice it until you're very close to it; other times, it makes itself known. It meanders seemingly from nowhere, curves and descends down into swampy area, draining into the Rutland Brook, thence to Connor Pond, the Swift River, and into the Quabbin. The water's form in this tiny spot is pleasant, innocent. This time of year, it's hardly flowing. I know it's there; that's enough for me.

I climbed up the hill, into the cliffside, to the special cave. I didn't know about this when I moved here, almost seven years ago. In March last year, right after everything shut down, James visited, and we spent hours in this cave, excavating a huge slab, building a stone wall to provide more shelter on the north side. I was supposed to be working remotely in front of a screen, but I completely blew it off to spend time with a friend, musing about stone age living as we tried to flake stone tools to dig out the slab. The immediacy of the activity felt primally satisfying – far more concrete than concrete.

At the end of April, Jacquelynn and I spent a night in the cave – a first for me. I'm almost embarrassed to say that I had never previously slept outside without some sort of tent or man-made enclosure. But I enjoyed sleeping in the cave, with only a few wool blankets on top of us, and hemlock bows for bedding. Between the enclosure of the cave blocking the wind, and the stream reassuring us below, we could sleep safely in a spot that hasn't been occupied for aeons.

Today, I intended merely to visit this sanctuary. Even though layers of wool allowed me to stay outside and sit on the ground, my toes started to freeze and would continue to remind me of my human deficiencies in this environment.

As I sat and listened, I suddenly felt an inexplicable fear of being attacked by a bobcat, including imagining a vivid scenario in which I would not likely survive. After snapping out of the daydream, I wondered if, perhaps, I had absorbed some of the anxiety of the herd of deer who had recently slept below the cave. I saw tracks of one curious individual who came up the hill and into the cave, before hastily descending the other side of the entrance. Was she spooked by something inside? I find it surprising that no large animals occupy the cave. There's some sign of chipmunk, possibly an ermine nearby. No, I suspect this cave has long been for human visitation. I didn't think too much about what I can't know; I just sat and listened until my toes told me to leave.

Generally, I avoid speaking out loud when humans can't hear, especially in the wild. It's not a fear, per se, but a concern for the odd feeling I get when I do vocalize to the world. All I can say is that it's an energetic feeling which leads me to be careful about what I say, and why. It doesn't seem to matter if it's a whisper or a shout – the energy still arises. As a result, I catch myself from saying the wrong thing. If this culture weren't so bereft, some elder could explain what ought to be said, and what ought not to. We're so cut off from the folks who used to hang around here, who probably had their own name for this stream, and these cliffs. I can tread carefully and listen and guess, but there's no guarantee that anything will be revealed to me.

Today, I asked my one question to the wind; the words echoed a lot further than I thought they would. Afterwards, there was some stirring, before it all settled down again. I can't expect an answer, but I'll keep listening, as these things tend to take time.

I left the cave to retread my path back home. Before leaving the Devil's Den amphitheater, I let out a howl. How could I not? Sometimes you just have to howl. Don't overdo it, though.

Passing back through the stone wall opening, I wondered more about this strange gateway. I took out my compass and observed that it's well aligned west-east with sunrise on Imbolc. It's a curious coincidence, though I can't prove any particular intention. I do know that these places in New England with Devil in their names were so called because they were associated with natives. Our forefathers – terrified of the wild, making new catastrophes wherever they set foot – sometimes would not even go near places of power they could neither subjugate nor understand. They'd name places after their devil, and scare children to keep them from establishing a proper relationship with the land. The end result is apparent: environmental destruction across the continent, along with generations of humans who are almost totally divorced from the landscape around us.

I don't need archaeological evidence to say that, for me, Devil's Den shall be an Imbolc place. As the light starts to return in winter, porcupines emerge from their den to assess the season. In Ireland, the divine hag gathers firewood to last her the rest of winter. Does she prowl through the woods here, sipping from the stream, or skating along the icy pool that lies above the cliffs? I don't know what guided the hands who built the strange stone wall, but I believe they were guided. I felt into my own stone intuition while piling rocks in the cave. I know these are crude, baby-steps toward reconnection with forgotten ways.

When I'm in these woods, I feel their dormancy. In the distant past, they may have been powerful, abundant. Then they were exploited, clearcut. In the past 100 years, they've mercifully been abandoned. Literally: a (not) bandon (control). They're not being controlled by humans, and with any luck, they never will be controlled again. The land is alive – some parts are thriving, while others struggle to survive in a changing climate. Now is a healing process for the land, as well as a time for rejuvenation, reinvention.

I would like to relate to this place, humbly and wisely, as a custodian rather than dominator. I'm not even sure how to learn to do it. But I feel so strongly that I must.

As it heals, this place may need a new name, befitting of its majesty. I hope, too, that the hills around me – currently named after clumsy men – will hint what their true names are.

I will keep listening, offering, and bringing the right humans into relation: to help heal this place, and us.